Learning to Read in Cantonese (Part 1)

Why does it feel so... hard?

I’ve been thinking a lot about what it takes to learn to read Chinese (using Cantonese) for a couple of years now, ever since I started this journey with my kids.

I recently decided it’s time to download those thoughts from my brain into writing, and am starting by dumping some of it here in two parts. This first part will break down why I feel like it is more difficult.

In English Science of Reading (SOR) literature, we prioritize teaching early readers the skills to sound out words, and then use that to draw upon spoken background knowledge and vocabulary to extract meaning.

The “other way” (which is frowned upon, as it goes against SOR) is teaching them to directly recognize words as a whole from its letters/word shapes (“sight words”).

What’s interesting though, is that this whole “directly read words as a whole” is what we adults do when we read.

Our literate adult brains do not spend much time, or cognitive energy, blending sounds for every single word on the page. Instead, we have developed automaticity in word identification.

We developed the skills to quickly, accurately, and automatically identify lots of different words by looking at the visual representation of a word. In fact, we get to a point where our brains don’t even process every word, and can extract meaning from a sentence just by scanning quickly.

Sounding things out

You can even try this yourself — try “reading” this sentence:

Wunz uhpawn uh thyme, thair wuz uh coddij en thuh fawrehsd.

Now try reading this:

Once upon a time, there was a cottage in the forest.

Reading the first one is all about “sounding” things out, and then drawing upon our spoken knowledge in English to understand what it’s trying to say. It takes much longer, and requires more energy than reading the second sentence.

The process of reading the first sentence is similar to what many early readers go through when they first learn how to read. Without a lot of reading experience, early readers don’t—can’t—directly identify words, so they have to sound everything out first.

Once our brains see certain words and common sentence structures enough times though (via more practice by virtue of reading more things!), we start to skip the “sounding out” phase and can identify words directly!

There is nothing wrong if we can directly and reliably extract meaning from print — it just means we can read fluently!

Okay… what is my point?

The process of learning to first sound out a word, is a means to an end.

The end result we want… is the ability to read. i.e. ability to extract meaning from print.

But before we can directly do that fluently in English, the ability to decode and pronounce words is useful for mapping the sound of an unfamiliar word to background knowledge in the spoken language to extract meaning.

This is why phonics skills are a useful tool in phonetic writing systems like English. It accelerates independent reading by teaching a small set of tactical decoding skills that will allow them to sound out most words without having to explicitly be taught how to say every. single. “sight word” individually.

These individual word pronunciations can then be chained into sentences, which too, draws from background knowledge of spoken language grammar to generate meaning, and thus — ✨comprehension✨

How does this work in Chinese?

Chinese, unlike languages like English, is considered to have an opaque orthography — that is, you cannot look at print and decode what it sounds like! There are some heuristics, but generally speaking, you have to be explicitly taught how to say individual characters.

Conventional wisdom says you need to know around ~2000 distinct Chinese characters to be considered literate in Chinese.

Contrast this with English, where there are:

26 letters

44 different “sounds” (phonemes)

~250 different “letter/letter groups” that map to above sounds (graphemes)

We’re looking at a whole order magnitude of difference between Chinese and English, in the amount of "things to memorize” in order to decode text and identify words!

Fortunately, some smart people invented phonetic systems (zhuyin and pinyin for Mandarin, and jyutping for Cantonese) that can be used alongside Chinese script to help map characters to sound.

These are often printed inline with Chinese characters in children’s books to help a budding reader “sound out” unfamiliar characters, and theoretically, extract meaning from said sound.

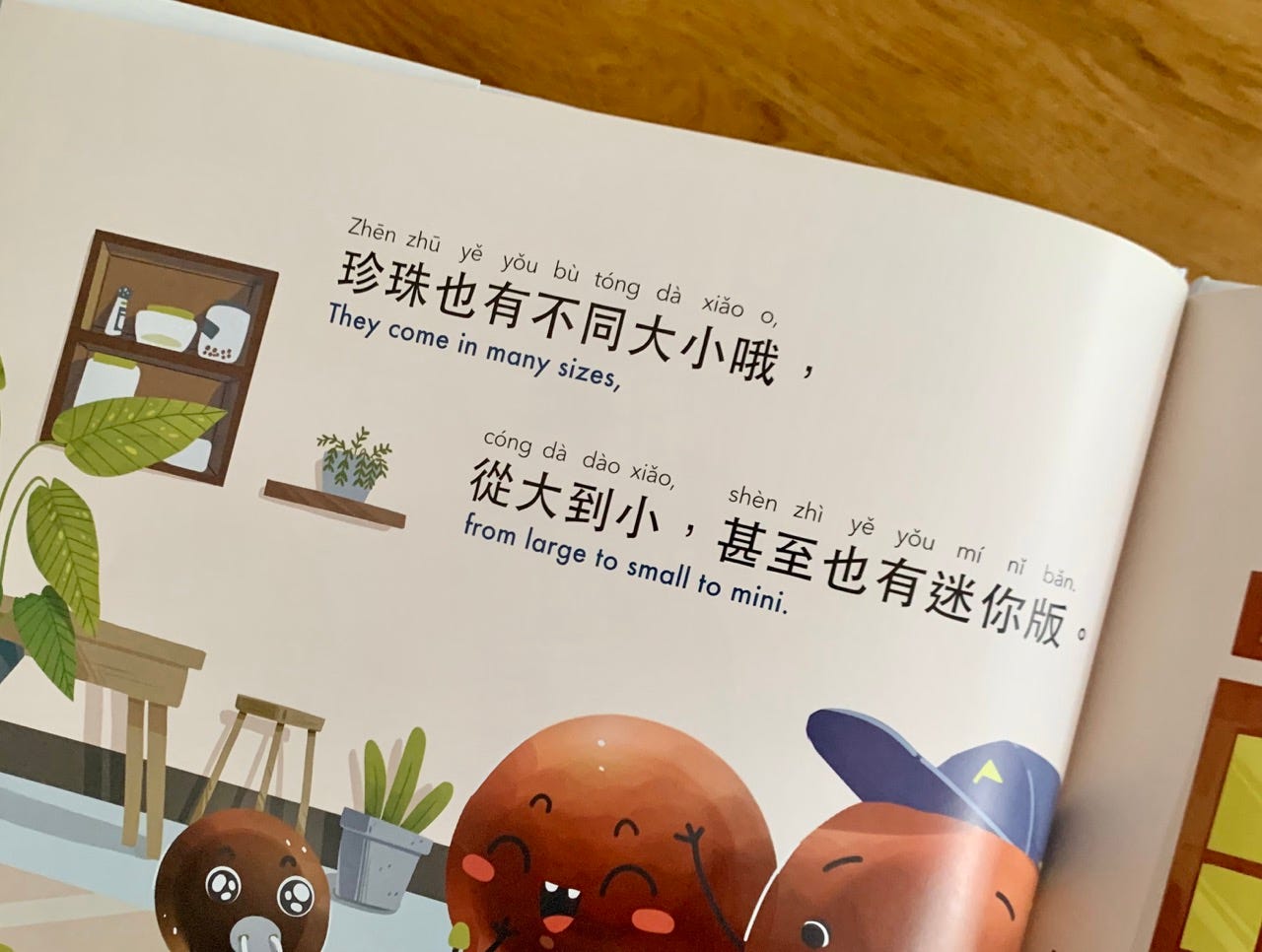

An example of inline pinyin found in I love BOBA! 我愛珍珠奶茶 by Katrina Liu

Except, it doesn’t quite work for Cantonese…

For one, inline jyutping (the Cantonese phonetic system) is not used by mainstream publishers at all. It is very, very, very rare to find jyutping in children’s books except in the self-published space.

But more importantly, even if we have jyutping available — it is often unhelpful to Cantonese speakers, because spoken Cantonese does not have the same vocabulary, syntax, or grammar as the standard written Chinese language.

In other words, even if an early Cantonese learner can sound out a sentence, they may still not comprehend the sentence because there isn’t spoken background knowledge to draw upon, to help with comprehension.

A simple example

Let’s take a look at a simple sentence in standard written Chinese:

我去告訴他吧。[English translation: I’ll go tell him]

When a Mandarin reader successfully sounds out this sentence, most kids will know what it means because it is a phrase often heard in everyday Mandarin speech.

An early Cantonese reader on the other hand, would still have no idea what was written even after sounding it out. They have to be explicitly taught what 告訴、他 and 吧 means.

“Extra hard” mode

Learning to speak a tonal language (9 tones!!) like Cantonese is hard enough.

Learning to read in Cantonese, is like playing a video game in “extra hard” mode:

Chinese has an opaque orthography (can’t “sound it out”)

Even when people try to mitigate #1 by inventing phonetic systems like jyutping, it doesn’t work for Cantonese because of the mismatch in spoken and written language

It is therefore why it shouldn’t be surprising that many ABC/CBCs can speak Cantonese fluently, but few have mastered reading, because it is indeed like learning a whole other language! It is hard.

So then, what are young Cantonese speakers to do if they want to learn to read?

I’ve been mulling over this, and there are few ideas to go about it, which I’ll cover in the next post (because this is getting long).

Stay tuned :)

Edit to add: You can now read Part 2 here.

Maybe not so much for younger kids, but things like the entertainment tabloids, magazines and some comics are written in more colloquial Cantonese.

Personally I do find it a bit hard to read the colloquial stuff but it's nice that it matches the way you speak. And even then, a lot of times different publications may use different Cantonese words for different things, which makes it really confusing at times.

Another thing in general I find that Chinese is not super rigid and a somewhat flexible language because of all the different regions and dialects, even if you start using Mandarin terms in Cantonese it's not always super weird, and I've found in recent years many words have moved into normal Cantonese usage too.