I know I still have Part 2 to this post to write — I’m working on it!

But I recently read a book, and felt super inspired to write down some thoughts around reading standard written Chinese and colloquial Cantonese.

I wanted to jot them down quickly, before that burst of energy passes and I no longer want to write about it anymore (which happens a lot, if you see my backlog of random thoughts I wanted to write about 🤪).

So here’s a quick (and somewhat random) post!

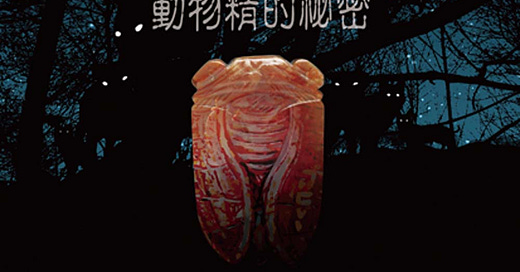

I recently read this book 👆 to practice my own Chinese.

《修煉》 is a YA (young adult) series that is apparently very popular. The story is set in modern times, featuring teen/tween protagonists, with elements of magic and Chinese history weaved in! It has been compared to the likes of Harry Potter and Percy Jackson books.

Right before this, I had juuust finished an (English) book on the science of how our mind reads.

That book’s ideas were still super fresh in my head, so my experience reading 《修煉》 was interesting, because it became a little “meta”: I was both trying to read this story, and also consciously noticing what my brain was doing while reading Chinese lolol 😬

Now that I’ve finished the book, here are some thoughts:

1) I’m getting faster at reading Chinese! Woo!

While I previously struggled to read some of my child’s easier “bridge books” (I had to read those very slowly, and it just wasn’t very fun), I found that I read 《修煉》 much faster.

My brain built up the story’s world in my head pretty well, and I got to “watch” the story unfold, instead of focusing on the text and language… and it was such a nice “flow” state to be in.

You know that feeling of “getting lost in the story”? Yeah — it’s so nice to experience that when reading Chinese too ❤️

I feel like whole worlds are now open to me when I can read Chinese novels this way (albeit just YA ones for now)

2) How my brain handles unknown words

There were still many Chinese characters in the book I did not know. If I had to put a concrete number on it, it felt like I didn’t recognize ~10% of the characters? I’d see at least 5+ characters on each page that I didn’t know.

But that didn’t really hinder my enjoyment or understanding of the book.

I’ve even managed to pick up meanings of new words!

One such word was 「聳」.

It showed up quite a few times, and it often appeared alongside 「肩」. Given I already knew what 「肩」 was… and with the available context, I fairly quickly deduced 「聳肩」 meant “to shrugg”.

Every time I see 「聳肩」 , I now know what it means! Even though I still don’t know how to pronounce 「聳」 😅

Reading Colloquial Cantonese

Other than standard written Chinese found in books like 《修煉》, I also read sprinkles of written colloquial Cantonese here and there, usually via social media posts.

What I find surprising, especially now that I’m venturing into reading full-blown Chinese chapter books, is that I’m actually slower at reading long passages of colloquial Cantonese, than I am at reading standard written Chinese (?!)

I tested this out with this wikipedia passage on Singapore Fried Noodles 👇

The first screenshot is in standard written Chinese:

While this next one is written in colloquial Cantonese 👇

I actually have a harder time reading the second passage 🤯

I understand both, but I’m slower at reading the latter, and much prefer to read the former.

Which… seems very counterintuitive, given I speak the latter and not the former regularly.

(Side bar: if you can read Chinese, which one did you find easier to read?)

A Possible Theory

One explanation for my preference for the first passage —

My brain learned to read Chinese in standard written Chinese.

After lots of practice reading Chinese written in this way… my brain created, stored, and strengthened these “orthographic” mappings (visual forms → meaning) over time.

These mappings doesn’t take just individual characters, but also groups of characters, or even entire sentence structures, and map them into meaning directly. My brain has mostly bypassed processing with “sounds” at this point. (Remember: this is how fluent readers read)

In contrast, I’m not as familiar with reading colloquial Cantonese. My orthographic mappings for that kind of writing is weak.

Headlines or short social media captions are fine, but I lack practice in reading “long form” colloquial Cantonese. Up until recently, very little long form content (i.e. published books) is written in colloquial Cantonese.

So my brain has to go back to the basics.

I can no longer just “scan” sentences quickly to extract meaning; I must sound out the sentence using my character knowledge, and then draw from my background knowledge of spoken Cantonese grammar to extract meaning from said sentence.

Which of course will feel slower.

Colloquial Cantonese vs Standard Written Chinese

These days, there are more books, especially children’s books, written in colloquial Cantonese.

My feelings on how to use them in our family, has always been a bit mixed.

I love that there are more options out there for different kinds of families — it’s always a good thing to have more books, and to have them accessible to more types of families, not just families with a caregiver who can read standard written Chinese!

I also love that the Cantonese community finally gets to immortalize er… document modern Cantonese vernacular by putting it in writing. I’ve always known there are LOTS of fun and clever Cantonese phrases — but I didn’t realize just how many — until books like Cantonese.jpg (now a fav book of mine) was made!

Plus, I absolutely love reading memes and jokes in colloquial Cantonese — I find them to be EXTRA funny 😝 Cantonese sayings are so intimately and uniquely tied to Cantonese culture. I often feel this indescribable connection to the writer, when I read posts in colloquial Cantonese.

Which to teach?

There’s always a question about what I should teach my own kids as a Cantonese-speaking family — standard written Chinese or colloquial Cantonese?

But, I’m thinking about it the wrong way. They aren’t mutually exclusive. I read both and I want both for my kids.

In the early stages of language learning, when kids are still learning how to speak and communicate in Cantonese, I need to use spoken Cantonese. This likely means narrating books in spoken Cantonese, not standard written Chinese, especially if it’s the child’s first exposure to the story.

But, if literacy is a goal, it is important to me that they know how to read standard written Chinese.

Mostly because I want them to be able to access the vast repertoires of Chinese literature!

And no, I’m not referring to boring stuffy Chinese “classics” or obscure poems, just so we can feel “hoity toity” about ourselves. There are SO many amazing contemporary kid-friendly titles, like this YA book I just read, to all kinds of manga, to fun non-fiction books…

All of these books (and imaginary worlds!) become open to them if there is fluency in reading standard written Chinese ❤️

Same Same But Different

As someone who can read both kinds of writing, I also find that standard written Chinese communicates things differently, compared to translating the same thing into spoken Cantonese and just putting that into writing.

The difference in “speech vs writing” exists even in languages like English. If we had just converted “spoken” English into writing, books wouldn’t be as good.

I know it’s hard to imagine what this means because the English spoken language “matches up” with the English written language.

BUT, as research shows… written English actually does look different from what we “naturally” say, even in seemingly “simple” children’s books!

As Anne E. Cunningham and Keith E. Stanovich wrote in their article in the Journal of Direct Instruction entitled What Reading Does for the Mind:

What is immediately apparent is how lexically impoverished is most speech, as compared to written language… The relative rarity of the words in children’s books is, in fact, greater than that in all of the adult conversation.

Put differently, children’s books use more complex and “rare” words than all of adult speech (!!)

In the same way, because the nature of colloquial Cantonese is… being spoken first, I suspect it too will naturally feel more “lexically impoverished” because we are taking what we say and "transcribing” that into printed text.

For example, there’s a 4-character phrase I came across in 《修煉》 that stood out to me: 「欲言又止」

It means… wanting to say something, but then hesitating and deciding not to.

Depending on the sentences and paragraphs used around this phrase, it can capture so much meaning and emotion… in just four characters. There is beauty and poetry in seeing it expressed so succinctly.

The equivalent in spoken Cantonese would be something like 「 想講,但係又冇講出口」

Sure, it has the same meaning on the surface, but it just doesn’t feel the same…?

And while we can sometimes say 「欲言又止」 in Cantonese speech, most books in written colloquial Cantonese will probably err on the side of not using such a 4-character phrase in writing, and choose a far more casual (ala “lexically mundane”) wording.

Ok, then what?

I know learning to read standard written Chinese isn’t going to be easy for a young Cantonese speaker at first, precisely because it doesn’t match up with our spoken language.

But, if I have my sights set on literacy for my kids (with the hopes that I can open up worlds to them through Chinese books), then it is important they can read standard written Chinese.

Once they have a solid foundation in reading standard written Chinese, then reading colloquial Cantonese can easily be picked up afterwards—even without any explicit instruction—because they will have enough character recognition, and a spoken knowledge base to draw upon.

It is a lot harder the other way around, imo.

Given I have limited time & energy to help my kids build literacy skills in a minority language, I’m going to spend it on creating that solid foundation in reading standard written Chinese.

For developing colloquial Cantonese “reading” skills… I will focus less on the actual reading of Cantonese words (嘅、啲、黃黚黚), and instead make sure I continue to provide LOTS of cultural input via speech, so that they can enjoy reading colloquial Cantonese memes and jokes in the same way I find them SO enjoyable to do now, thanks to my background knowledge in Cantonese vernacular ❤️